|

April 2, 2007

Cornell physicist Kenneth Greisen, cosmic ray

scientist and Manhattan Project participant, dies at 89

Kenneth I. Greisen, Cornell professor emeritus of physics and a

pioneer in the study of cosmic rays, died March 17 at Hospicare of

Ithaca. He was 89.

David

Koch |

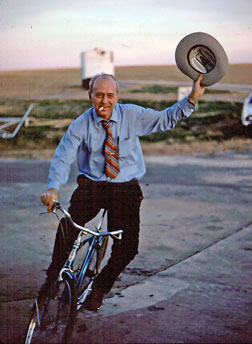

| Ken Greisen in 1971, at the National Center

for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Texas. Greisen conducted

experiments using gamma ray telescopes flown to the top of the

atmosphere with large balloons. Here, he celebrates a flight which was

the first to detect pulsed gamma rays with energies greater than 200

mega-electronvolts from the pulsar in the Crab nebula. Click photo for

full-size picture. |

Greisen, described by colleagues as a man with "quiet and

unobtrusive self-confidence," is best known in the world's science

community for his work detecting and understanding the protons and

other particles that shower Earth from galactic and extragalactic

sources. In 1966 he predicted an upper limit to the energy of cosmic

rays that reach Earth from distant galaxies; this limit, calculated

independently by Russian scientists Vadim Kuz'min and Georgiy

Zatsepin, is known as the GZK limit and remains a subject of intense

research today.

Greisen also worked on instrumentation for the Manhattan Project in

Los Alamos, N.M., from 1943 to 1946. He witnessed the July 16, 1945,

Trinity explosion and recorded his observations from a desert station

10 miles away.

"Suddenly I felt heat on the side of my head toward the tower,

opened my eyes and saw a brilliant yellow-white light all around. The

heat and light were as though the sun had just come out with unusual

brilliance," he wrote. "A tremendous cloud of smoke was pouring

upwards, some parts having brilliant red and yellow colors, like

clouds at a sunset. These parts kept folding over and over like dough

in a mixing bowl."

Greisen was born in Perth Amboy, N.J., on Jan. 24, 1918. He earned

a B.S. from Franklin and Marshall College in 1938 and came to Cornell

as a graduate student under pre-eminent cosmic ray scientist Bruno

Rossi. For many years his first paper, "Cosmic Ray Theory,"

co-authored with Rossi in 1941, was the primary source of information

about the field. Greisen earned his Ph.D. in physics from Cornell in

1942.

After the Manhattan Project, Greisen returned to Cornell as an

assistant professor of physics. In the 1960s he invented a detector

that used air fluorescence -- the phenomenon in which charged

particles passing through the atmosphere excite gas molecules, which

re-emit a portion of the energy as visible or ultraviolet radiation --

to search for cosmic rays near and above the energy of the GZK

limit.

Greisen designed and built an array of the detectors around Ithaca;

that design, refined by physicists at the University of Utah, led to a

detector called the High Resolution Fly's Eye (HiRes). On March 6,

2007, the HiRes collaboration reported the first solid evidence for

the suppression of cosmic rays with energies above the GZK limit. It

is also the model for a major new detector currently being built by an

international collaboration in western Argentina.

In the 1960s and '70s, Greisen conducted experiments using gamma

ray telescopes flown to the top of the atmosphere with large balloons.

One of these detectors, flown in 1971, was the first to detect pulsed

gamma rays with energies greater than 200 mega-electronvolts from the

pulsar in the Crab nebula.

Greisen helped found the High Energy Astrophysics Division of the

American Astronomical Society and served as its first chair in 1970.

He was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1974 and chaired

Cornell's astronomy department from 1976 to 1979.

He was also Cornell's university ombudsman from 1975 to 1977 and

dean of the faculty from 1978 to 1983. A dedicated teacher, he worked

with the Physical Science Study Committee in the late 1950s to improve

high school science courses; he also helped redesign physics courses

at Cornell.

"Ken was a wonderful, gentle person," said Saul Teukolsky, Cornell

professor of physics and chair of the physics department. "It's no

wonder he was so successful as university ombudsman. But at the same

time he was at the top of his field in cosmic ray physics, and his

work continues to shape the field today. Ken was also a pioneer in

reforming the way physics is taught, both on the national scene after

the launch of Sputnik in the 1950s and in the introductory courses at

Cornell."

His former students recall a thoughtful, deeply respected mentor

who seemed at ease both solving and explaining the most complex

problems. "Ken became a model for me of a brilliant and incredibly

strong physicist who was kind and generous," said former student

Murray Campbell, now the William A. Rogers Professor of Physics at

Colby College.

Greisen is survived by two children and an extended family. A

memorial service will be held in the Kendal Auditorium, Kendal at

Ithaca, April 22 at 3 p.m.

##

|