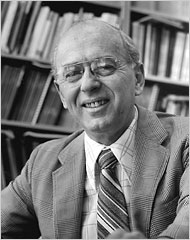

Kenneth I. Greisen, a physicist who helped broaden methods of studying cosmic rays, including sending unmanned balloons into the upper atmosphere and planting detection devices in salt mines, died on March 17 in Ithaca, N.Y., where he was a former dean at Cornell University. He was 89.

Kenneth I. Greisen.

Dr. Greisen’s death was confirmed by his family.

As a graduate student at Cornell in the early 1940s, Dr. Greisen began research on cosmic rays in an effort to better understand their sources, energy and composition. The rays shower the earth with particles. A frequently observed source is the sun, although other rays and radiation constantly arrive from beyond the solar system.

Dr. Greisen, Bruno B. Rossi and others placed devices to detect the protons and other charged particles at sites on Earth’s surface and in deep-earth stations, including one set up in salt mines beneath Ithaca.

In 1971, in an innovative high-altitude experiment, Dr. Greisen observed gamma rays at 107,000 feet, when he and fellow scientists attached a radio telescope to an unmanned balloon. The experiment was intended to measure particles sent forth by a pulsar in the distant Crab Nebula, about 6,000 light-years from Earth.

Earlier, in the 1960s, Dr. Greisen developed an influential theory about cosmic rays and how their energy levels change over distance. Formulated with two Russian scientists, Vadim Kuzmin and Georgi Zatsepin, the theory was called the GZK Limit, its name a combination of the scientists’ initials.

The theory holds that incoming rays are affected by a background of microwave radiation still lingering from the Big Bang. In effect, it predicts that rays with energy higher than the limit would be filtered, or reduced, before reaching Earth. The theory has both critics and adherents and is still being tested, following findings from detectors in Japan of rays surpassing energy limits proposed by the three scientists.

Kenneth Ingvard Greisen was born in Perth Amboy, N.J. He graduated from Franklin and Marshall College and earned his doctorate in physics from Cornell in 1943.

He was dean of Cornell’s faculty from 1978 to 1983. He also served as university ombudsman and chairman of the astronomy department. After helping to revise Cornell’s physics curriculum, he became a professor emeritus of physics in 1984.

Dr. Greisen, who was a longtime resident of Ithaca, is survived by a son, Eric Greisen, an astronomer, of Socorro, N.M.; a daughter, Kathryn Greisen of Columbus, Ohio; two stepdaughters, Heather Wiltberger of Marshall, Va., and Lois Wiltberger of Arlington, Mass.; a stepson, Paul Wiltberger of Arlington, Wash.; and two grandchildren. His first wife, Elizabeth, and his second wife, Helen, died before him.

From 1943 to 1946, Dr. Greisen worked on the Manhattan Project in Los Alamos, N.M. He helped prepare detonators for atomic testing and witnessed the first test of the bomb, on July 16, 1945, in a close-quarters experience that he found visually stimulating but less daunting than expected. In the days before the test, when driving to the secret testing grounds, a speeding Dr. Greisen was pulled over by a police officer, but he had a more pressing concern. In the trunk of the car were 92 detonators ready for the test, and he worried about coming up with an explanation. To his relief, the trunk was not searched.

“Fortunately,” Dr. Greisen recalled, “he just gave me a ticket.”