Barry Clark's Blog

There was a symposium in Santa Fe, on the galactic center. I was only interested in some of it. So I thought I would try commuting, via the Railrunner, for a couple of the days. Yes, it feels like a normal commuter train; the train keeps very closely to its schedule, there were a fair number of bicycles on board, and everybody seemed to know one another (and grumble about their bosses to each other). But I do not think I'd like to live in Socorro and work in Santa Fe. I set the alarm for 4:15, left for Belen at 4:45, caught the 5:39 out of Belen, arrived in Santa Fe at 7:48, walked the half mile or so to La Fonda Hotel, where the meeting was being held, and got there in time for their continental breakfast before the meeting started at 9:00. I skipped the last couple of talks and left the hotel at 5:00 to catch the 5:30 to Belen, arriving 7:38, home about 8:30. Makes for a long day. That was Monday. I skipped Tuesday, and only went to a half day Wednesday. But I didn't get out in time to catch the 1:02, and, in the middle of the day, commuter trains are rather far apart. I caught the 4:15, and got home by 7:30. A bit better. Last two days, I drove and spent the night in Santa Fe. I was too late getting organized to get a room in La Fonda, so I spent the night in my usual Quality Inn at a quarter the price. The Quality Inn is generally OK, but a bit short on maintenance staff (bedside lamp inoperable, closest outside door to my room wouldn't open to key card).

Of course, the government shut down on the Tuesday. NRAO is not a government agency, though all the money comes from the government, so we didn't shut down. Last government shutdown, in the '90s, NRAO managed to ride through it, using money given for purchases in the previous fiscal year for operations instead. This time that bought us four days. NRAO shut down as of the Friday. Building was locked, VLA and Green Bank Telescope shut down, and we were told to stay away.

Shutdown notice came with instructions on how to apply for unemployment insurance. Included a thoughtful note that if you were away on travel, you could come home.

I guess I survived without going to work. I devoted a massive amount of free time to organizing all the paper in my home office. This involved dragging all the miscellaneous papers out and putting them on the floor, which they covered to a uniform depth of about six inches. I then wandered over the mass barefoot, picking up the various items I happened to be interested in (and finding items I hadn't collected on the last pass). A few days of this resulted in a collection in which I might actually be able to find an item and in perhaps a dozen small grocery bags of trash.

There are still a couple of boxes of stuff that I didn't go through because it was sort of organized before I started. It would have been fun to go through that, but the government finally got its act together, and I got to go back to work.

Went to Salt Lake City for Christmas. I eventually decided to take Baxter, and drive, despite the strict anti-pet thunder in the terms of the house we rented. We took two days at it, and took a couple of hours to visit Arches National Park, which has always been one of my favorites. National Parks are generally rather down on dogs, too, but they didn't seem too obnoxious about it. And we didn't really get far out of of the parking lot - I'm afraid I've come to an age where it matters that the trails were snow packed and icy.

So we got to SLC early afternoon and I got Baxter settled in a kennel in North Salt Lake. When I left, he was busy wrapping the female attendants around his little paw - he can detect a likely sucker from a mile away. I then passed on to our home away from home, and found it full of Christmas Tschotskis. When Thea arrived. she felt it necessary to make a census of Christmas trees. She counted twenty, between two inches and eight feet tall.

I picked up Marin, Thea, and Jasper late that night, and we got to bed around two. Bill came in about eleven the next morning, and Doree and Kevin drove in about two or three, so the cast assembled pretty quickly. Judy had arrived on her own, and stayed at a hotel, before it was realized that we had plenty of room at the inn.

That night the Provo and SLC Clarks joined us, and we sent out for pizza at a local eatery of some repute. We sent Bill to get it - three large vegetarian pizzas, and three super-sized meaty ones. Bill estimated fifty pounds of pizza. We had leftovers. After all, four of the two dozen or so of us were very small. But with breakfast, lunch and snacks the leftovers were pretty well gone by the time we left.

The following night, Christmas Eve, Catherine had us to Orem for dinner. On the way we stopped to see Bill, aka Clark. He now lives in a small tract house on a cul-de-sac three or four miles south of the Temple. Two females live with him, receiving, he says, free rent in return for various services. Sounds like a good arrangement to me. Anyway, eight of us descended on him, and created a hubbub. He says it really isn't his hearing that's going, but the ability to sort out words from voices, which made him a little slower to respond than last time I visited him. Young Bill, though, says he seemed little different from when he last visited, six or seven years ago. Anyhow, he seems to be functioning at considerably better than a take-care-of-myself level.

So in Orem, Catherine provided of two kinds of soup, various raw vegetable things, and some excellent bread.

Christmas night, the crowd came back to our place, and had a spiral cut ham and various contributions from others of potatoes done a couple of different ways and various vegetables.

Christmas morning we had the traditional strada, which I thought came out exceptionally tasty, probably because the bread was exceptionally good. But with only eight people, the Christmas morning events seemed depopulated relative to other activities.

I see that so far, I've been talking mainly of food. To get to the second most important aspect, we had a good introduction to the great grandkids - Wednesday, 3, and the boys, twins Simon and Nicodemus, and Richard, all just over one. Richard would be walking, only his crawl is so fast and efficient he doesn't see the need for more upright locomotion. Emily's twins are still feeling their way a bit. Marin's children rather took them over, and their parents were happy enough to be relieved of them for a while. Wednesday provided her own program, and didn't have much to say unless it wasn't going quite as she wished. With that sized group, even without the ever vigilant Clarkbergs, little people could wander around with much chance of getting into trouble (despite his best efforts, I don't think Richard ever got higher than the third step on the stairs before somebody concluded they should corral him).

Thursday we reprieved Baxter from his kennel, and the older folks took him for a nice walk around the Utah state capitol, whilst the younger set went tubing in the mountains to the east. Meanwhile, Marin had discovered there was an Ethiopian restaurant near where we were staying, and she said she hadn't had good Ethiopian food for years. So we ate Ethiopian that night, again in massive quantities. Basically it is a bread which looks rather like the sponge rubber pads you find in car seats, but which tastes pretty good, especially after being soaked with the juices from the various stews and vegetables put on top of it. No forks - one eats with ones hands. I rather think asking for a fork would be even more gauche than in a authentic Chinese restaurant. Some people make the excuse that they just can't manipulate chopsticks, but few claim they can't manipulate their fingers.

Friday we made the obligatory visit to Temple Square. I may be misremembering, but it seems to me that the helpful, conservatively dressed young people were more willing than in times past to let us wander the exhibits on our own, without offering to help, to explain, or to provide references. In the visitor center they had a miniature reconstruction of Jerusalem as it was at the time of the Jewish War, which I dearly would have loved to have had at hand when I was reading Josephus's account of that war. We toured Desseret House, Brigham Young's house and office on the corner of the square, which I had not done before. This was handled in the more traditional way of forming groups and passing them along from one pair of young elders (!) to another. Very efficient, but not as deft as the management in the main Visitor Centers. They were very carefully neutral in handling the fact that when they referred to his wife, more than one name kept showing up. This doesn't bother me in principle. My chief gripe with polygamy is its inequality - that the rich guy has a few wives implies that some poor guys who would like one have none. (Muslim polygamy bothers me for the same reason.) And the modern Mormon throwbacks who practice polygamy are often sufficiently nuts that abuse arises in many other areas, not necessarily induced by polygamy itself.

Saturday morning, I took Bill to the airport early, then came home, had breakfast, and took Marin and hers. So by ten o'clock I was the last of the invaders. Faced with the choice of fiddling the day away visiting some of the indigenous Clarks or retrieving Baxter from his kennel, and getting a start on going home, I decided to do the latter, at least partially impelled by the fact that I felt a cold coming on. So Baxter and I set off for Socorro. I had intended to stop for the night maybe around Cortez, but my cold was annoying enough that I really didn't want to face locating and settling down in a motel, so we ended up driving on home, getting to Socorro about 11. I suspect we really did not stop for a walk-around nearly as often as Baxter would have preferred, but he is a polite little dog and didn't mention it.

I essentially did nothing on Sunday and Monday, and thought I was getting over my cold, and went to NRAO on Tuesday. But Tuesday night saw me plunged into the Mother of Colds. Three days during which setting out food for the dog, and maybe getting a little something to eat for myself, seemed barely sustainable demands on my time and available energy. On Friday I worked up the energy to go see the doctor. I told her it must be influenza, that surely rhinovirus could not make me feel so bad. She said "Yes it can". but consented to take a nasal swab just in case. That and the trip to the pharmacy took an hour and a half. And a two hour rest after that restored me sufficiently that I could take the medicine she prescribed.

Friday, I also had the energy to clear up something that had been bothering me for the last two days - I picked up the dirty underwear from the bathroom floor. But taking care of the other one, emptying the thrash can by the recliner and picking up all the used tissues around it that had bounced off, had to wait until I had a little more energy, Saturday morning.

While I was sick, I had some pretty weird dreams. I remember three. One was a rerun of the temple square walk. I think I got the two versions pretty well separated. I'm pretty sure the one inch black cubes that occasionally made a comment about what we were looking at, or held a muted conversation with the young men in white shirts and ties, were from the dream version.

Another dream appeared to be some sort of competitive geocaching game, involving people crashing through the underbrush at breakneck speed at the behest of a GPS held in front of them. Needless to say, I didn't do well at that game. Nor did I do well in the third dream, which involved me being sent to a madrassa to memorize the Q'ran. I apparently said I thought it might be easier if I learned enough Arabic to know what I was memorizing. This was considered a Bad Attitude.

So anyhow, I seem to be recovering, after a fashion, and am back in business at the usual stand, though I still have a pretty messy house I need to tackle sometime before Ms. Reyes comes and sees it Tuesday morning.

I've always found it easier to travel in cold weather, because a coat supplies sufficient pockets for boarding passes, passport, book, etc. A friend, who travels a lot, recommended a purse. So I went to Walmart and bought a purse. It worked very well, and was a lot less bother than a minimal carry-on. And even had room for a pair of underwear for use mid course.

Went through a lot of security screenings. Albuquerque, of course; San Francisco, because the trip from United Express to the International Terminal went through an unsecured area; Seoul, God knows why, and Singapore. At the last, only some destinations had security screening, and I couldn't figure out the system for which, but Ho Chi Minh City was one. I stayed in the transit hotel in Singapore (for about six hours). First time I've stayed in a room without a window, a little cubic box. When I turned out the light, the only illumination was from the green light on the smoke detector.

We are so indoctrinated that the name of the place is now Ho Chi Minh City that I was quite shocked when the pilot announced that this was flight SQ 172 to Saigon. There is still a fair amount of usage of Saigon for the city, neighborhoods, and, of course, for the Saigon River.

So I got to Ho Chi Minh City, and was duly picked up by Road Scholar, and taken to the Grand Hotel, which is quite nice. Vietnam is one of those countries with a currency such that a unit is not worth much. The first clue to this was that as part of the check-in package at the hotel was a card for a discount at their spa, for half a million dong. Although smaller bills sometimes shown up, the smallest bill you usually see is 1000 dong. And inflation continues to run; our guide said 22% per year. There are rich people in Vietnam, despite the ideology. Our guide referred to them as trillionaires.

Our guide's name is Doung, pronounced Young (she says in some parts of the country, it is pronounced Shoung). She is a small woman (just under 1.5 meters (5 ft) tall - she mentioned a job that required a 1.5 m height, that she didn't get, falling under by a couple of centimeters), but with a outgoing, take-charge character that makes her a good tour leader and just a terrific person to know. In fact, she reminds me of my niece Donna, living alone, in charge of her life, loving her pets (a bit more than Donna - three dogs, three cats, and a turtle).

After arriving at the hotel, I had a nice nap, then met the core part of the tour group for dinner in the hotel restaurant. There were three couples, a woman of very self confident mien unaccompanied by her husband, and me. I suspect I'm the oldest, but the youngest are already in, ahem, "advanced middle age".

The streets of Ho Chi Minh City are filled with motorcycles and scooters, easily outnumbering the cars. (The cars still have the greater weight of moving metal, though.) Our guide said that a good Japanese scooter costs only $1,000 US equivalent, and cheap Chinese knockoffs for little more than half that. True volkstransport. The scooters fill the interstices in the traffic, like water in a bed of pebbles. Any time there is a gap between two cars, there are three bikes in it. Traffic is heavy. Young says there is no longer a rush hour in Ho Chi Minh City. It is rush 24/7. Crossing the street is about the same art as in Beijing. You yield to vehicles, like buses and trucks and some cars, that look too ungainly to dodge you. For the rest, you look like you know what you are doing, and move confidently and steadily, otherwise ignoring their existence. The sea of motorcycles will part before you.

So first thing in the morning we went to the University of Humanities and Social Sciences for a lecture by a professor. A typical professorial talk, with the material carefully ordered so that if you take good notes, they are perfect study media for the test. But not really geared to telling us what we wanted to know. Lots of stuff about the ethnic makeup of Vietnam, but not that much about how it all fits together. Then we met with a group of students, Japanese majors (why? Idunno) who spoke excellent English. The student I talked to was appalled to learn that I live two thousand kilometers from my nearest child, and that I only see the children once or twice a year. She said that would not be acceptable in Vietnam.

The afternoon we went to the War museum. It was about as you might expect. Lots of pictures of happy families, with a caption giving the date and location of the American bomb that wiped them out. There were two pictures I found particularly touching. One was a little girl, silhouetted in front of a burning village. The caption said something about revenge, but that was not what I read in her face. What I saw was apprehension and a tremendous sense of loss. The other photo was of a boy, maybe eight years old, in a forest defoliated by agent orange, a barren contrast to the green that surrounded us today. It's always the kids who get to me - "War is not good for children and other living things." They had a room filled with pictures of children with birth defects, attributed to agent orange, which I thought went too far. Even if the attribution is correct, I think it is wrong to put these kids on display to make a point. The museum also had a "tiger cage" display. It seems that a similar prison technology was employed by both sides.

Next day we had a free morning. I used it to go to an art museum, navigating myself by map. Turns out that's a lot harder when the street names mean nothing to you, a random jumble of letters. The art museum had two wings: modern and classical. The ticket lady informed me I should go to the modern wing first. There, the reception lady told me to go to the second floor first, and, obedient as usual, I did so. This floor was all post-war stuff, and was about as one might expect. The piece I liked best was a sculpture named "The people of [some village] hate their enemies." A stylized figure with open mouth, clearly screaming "death to the invaders". The first floor was stuff done during the war, and was not as subtle as that. The other wing was in a bit of a mess. They had had an exhibition of Indian art, which they were in the process of taking down. I wandered between construction sites to see ancient pottery and 18th century bronze, neither of which turned me on. They had some Vietnamese impressionists, which seemed to me a pale imitation of European impressionism, except for one large landscape, which I liked because of the extensive impasto. I just like impasto.

After lunch (pho, of course) we went off to our cruise ship. The name on the bow is "Toum Teav". However the boat is usually called "Toum Tiou". But it is also called "Teave". I rather think there was some explanation for the multiple names, but it didn't stick in my head. The ship has ten staterooms for passengers, occupied by thirteen tourists and our tour guide. The crew is about the same number, with a bartender and waitress ready to react to our most trivial desire. The captain is a delightful man of French-Vietnamese extraction who gives the impression that his principal function, maybe only function, is to make sure his passengers are tempted by vast quantities of really, really good food. Typical breakfast: crepes, fruit (jackfruit, pineapple, and lichee (not really lichee, but a close relative)), croissants, eggs to order, and yogurt.

We set off down the Saigon river, to the southeast, for a couple of hours, nearly to the South China Sea, where we parked for the night. The Saigon area is pretty busy, with docks, manufacturing plants, and all sorts of businesses along the banks. There was a lot of water hyacinth in the river, floating upstream because that was the way the wind was blowing. There was a lot of barge traffic. The most common load was dirt. Actually, there were three kinds of loads that looked like dirt. There was real dirt, dredged from the bottom of canals, sent to Saigon, or to farmers along the river, for use as fertile topsoil. Then there was a grayish sand, used for construction of foundations and in other places where looks are not important. And then there was the fine yellow sand, used for construction, or for export. The sand is dredged from the river bottom.

The next day started our aggressive touring. The Mekong is really the cornucopia of Vietnam, producing rice (for export as well as domestic use), a great variety of vegetables and fruit, fish, and flowers. Young has a great fondness for markets, so we saw a lot of markets - vegetable markets, fish markets (most of the fish still alive, to be pulled from their tub and whacked on the head and butchered, to be ready for the next customer). Chicken, separated into parts - chicken feet, chicken wings, chicken thighs, chicken breasts (which Young says are considered dull and less desirable). Fruits of all kinds, many of which I had never seen before - jackfruit, rose apple, oranges with green rinds, kumquats (as sweet as the ones from California, though the vendors laughed at us for sampling such sour fruit), pomelo, and dragon fruit. Vegetables, some familiar - corn on the cob, potatoes, jicama - some totally unfamiliar - water hyacinth leaves, banana flowers, river spinach, lotus seeds. Perhaps the most outre, in the meat market, you could buy rat. And there was a large basket of a great delicacy, rat testicles.

We went to a family owned factory making rice and coconut products. We saw the process for making rice paper, for wrapping spring rolls, and rice noodles. Young said that in years gone by, the latter was a big job - they took the egg roll wrappers and cut them with scissors to make noodles. The factory made coconut chews. They were proud of their electric mixer, a great labor saving device, but still there were a couple of ladies sitting there, individually wrapping coconut chew candy (shades of Lucy and Ethel). They made rice crispy treats, from start to finish. Start was putting fine river sand in a large copper wok. When it was hot, the sand flowed like liquid (at first I thought it was hot oil). Then they threw in a scoop of rice, and started to stir vigorously. Soon the rice began to pop; voila, rice crispies. They screened it with a fine screen to return the sand to the wok, then with a coarser screen to remove unpopped kernels. They mixed it with a sweet binder. and rolled it our on a cold stone. They cut it into squares, and packaged it in plastic.

We also visited a fish farm. This was a small scale operation. It was a house on floats, anchored. There were nets strung under the house, dividing the area under the floor into three or four pools, each with a different age of fish. The fish food was made from rice polish, the stuff removed to make brown rice into white. When a scoop of fish food was tossed into the pool, the fish converged on it dramatically, crawling over each other to get to the food. The general effect was of opening a dish washer in mid cycle. (Young assured us that we would never be served such trashy fish on Toum Tiou.)

These side expeditions were conducted mostly by launch. Docking Toum Tiou is a pretty major operation. So a modest sized launch, with maybe twenty folding chairs on its deck, would pull up beside Toum Tiou, and we would clamber down a ladder into the launch, which would drive us to shore and ground itself, typically on a set of concrete steps, and we would then step off onto the shore. This is doable, even for such as I, but happened enough that the tour is classed as medium energetic. And of course, everybody was very solicitous of the decrepit old man. There were kids offering to help me who didn't weigh a quarter of what I do.

One time the Toum Tiou actually docked was at the Victoria Hotel, acknowledged to be the best hotel in the Mekong. Young said that previous tours had dinner at the hotel, but they quit that when tourers said the food was much better on Toum Tiou. Which I believe. There are a good number of Catholic churches in the Mekong, leftover French influence. Young said Vietnam is about 15% Catholic. There are a similar lot of Buddhists, and we were shown several temples. And there was a rather strange group called Cao Dai, which claims to combine the tenets of Catholicism, Buddhism, Tao, Confucianism, and Islam. But, she says, the biggest group is the Free Religious, which I gather corresponds to the American appellation of "None." But whatever the religious affiliation, everybody has an obligation to their ancestors. On the death anniversary of your parents and grandparents, you must give a party for your family and for their friends. Young called this ancestor worship, but is not quite what one usually thinks of being ancestor worship. And the obligation ends with the third generation.

Young is a really remarkable person. She was born in a village in the central highlands a few years after the war. The village was part of South Vietnam, and loyal to its government. So after the war, the unified government was not in any hurry to do anything good for the village, and the whole village was desperately poor, her family among them. To illustrate their desperation I need only say that part of her family's subsistence was recycling land mines. They dug out shell fragments and land mines. For the land mines, they took them apart, and sold the metal and the explosive separately. The explosive was bought by fishermen for dynamiting fish. One day, on her way to school she heard a loud boom. A neighbor in the same trade had a mine go off while they were cutting it open. He and most of his family were killed. Young's father said "No more mines." He'd rather they starve. Her father became alcoholic, she says because of his treatment after the war as a Southern loyalist. Her mother died when she was fifteen. But she did well in school, and was one of a very few from her village school to gain admittance to the University. Somehow with the aid of a better off family in Ho Chi Minh City, she managed to find a way to pay for it, and graduated with a degree in being a tour guide (this sounds a little strange, and I may have got it wrong). That such a background could produce the woman we see before us stretches my ideas of human fortitude.

We proceeded with two days of steaming more or less all day, crossing the Cambodian border and tying up at Phnom Penh. The countryside becomes rather different in Cambodia. There is much less rice cultivation, partly because there is less flat land for paddies, partly because the river banks are higher, four or five meters, so that much more massive irrigation works would have to be built to flood them. On the other hand, we saw large fields of corn, which we had not seen in Vietnam. There were orchards; I couldn't identify the trees from the boat, except, of course, for coconut. (Once I was thinking "that's a good looking field of corn", and then I saw a man in front of it. Oops, that's a good looking field of bananas.) At some places there were pipes leading into the river. I suspect these were feeds for electric pumps drawing water for irrigation.

The first couple of days were spent trying to explain the Khmer Rouge to us. This is not easy. First, both the Vietnamese and the Cambodians painted Norodom Sikhanouk much more positively than I remember from the US; soon after he became king, at age 18, he essentially negotiated the independence of Cambodia from French rule. The US story was that he then essentially retired from politics, expecting to be a constitutional monarch; the story here is that he was deposed and exiled by a coup led by General Lon Nol, sponsored by the American CIA. He asked for support from the Chinese to regain his throne. (Somehow, the concept of a hereditary monarch discussing how to get his throne back with Chou En Lai seems strange to me.) The Chinese recommended he go with the only existing organization opposing General Lon Nol, the Khmer Rouge, waging a guerrilla from the depths of the forest. And having the King on their side was a powerful recruiting tool, and the Khmer Rouge grew and eventually prevailed. Now here it gets hard. We had a lecture by a lady who came with a UN mission fifteen years ago. Her story was that the Khmer Rouge were paranoiac about the CIA, to an insane degree. So many people were denounced as probable CIA (or KGB), that the fear went from fear of the CIA to fear of being denounced, and such was that fear that people started denouncing others whom they thought might possibly denounce them, and the country shuddered to an explosion of paranoia, feeding on itself. The Cambodian Phnom Penh tour guide had a line much more like I had heard before, that the Khmer Rouge had a program to return Cambodia to the conditions of the great Khmer Empire of the fourteenth century CE. Most of the population were to be simple peasants, with a tiny percentage of leaders, and that lawyers, doctors, engineers, and businessmen were parasites on the state, to be retrained as agricultural laborers, or eliminated altogether. Our guide (probably Sherek, but maybe Jerek or Derek) said his father was an engineer, but survived because he came from a farm family and knew how to work in the fields. He said that when his parents told him about what it was like under the Khmer Rouge, or even when his older brother told him, he simply didn't believe them.

When the Khmer Rouge first succeeded, driving General Lon Nol into exile, the first action they took was to evacuate Phnom Penh, telling the people that Cambodia would be invaded and Phnom Penh seized by the CIA. People were told to take three day's food, and walk to a village in the countryside. If they had family in a village, go there. If not, the Khmer Rouge would tell them where to go. Some villages were 300 km from Phnom Penh. On three day's food. Phnom Penh became a ghost city, uninhabited.

Denunciation became a major industry. We visited Tuol Sleng prison, S21, in Phnom Penh, one of the largest. It was a repurposed high school. The third floor became dormitories, with prisoners shackled to long iron bars, fifty or more in a five by fifteen meter room. When it was time for the prisoner to be "interrogated", they were brought downstairs to a one by two meter holding cell, hastily built subdivisions of classrooms. The interrogation rooms were a standard classroom. The interrogator sat behind a desk and would say "Are you CIA or KGB?" "Neither" was not an acceptable answer. That or any other unacceptable answer led to torture. On exhibit was a device for pulling off fingernails, and the crossbeam where prisoners were suspended upside down with their heads in a bucket of sewage. Just saying "OK, I'm CIA" did not stop the torture. The questioner then turned to "Who are your associates?" Those who confessed under torture, being guilty, were sent for execution. Those who did not were considered intransigent and were sent for execution. There were those who confessed, but did not accuse associates; this they knew would lead to execution, and stop the torture.

A painter or musician might be kept by the commander of the prison, because the commander appreciated art. An engineer might be kept for his usefulness in maintaining the mechanical systems of the prison. But only until the next prisoner of similar skills arrived.

Prisoners were sent for execution by truck, thirty to a truck, to the Killing Field. We visited one of more than three hundred. The prisoners were unloaded from the truck, usually already blindfolded and their arms tied. They were made to kneel on the edge of a mass grave, and were struck on the back of the head by a man with a heavy stick or an iron bar. Another man, standing in the grave, would look for signs of life, and, if necessary, cut the victim's throat.

The camp was staffed to handle about three hundred executions a day. If more than that arrived, there was an on-site prison, to hold them until the next day.

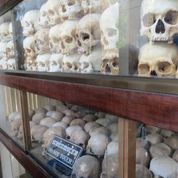

After the end of the Khmer Rouge reign, the graves were excavated, the bones burned (per Buddhist procedure) and the skulls moved into a memorial stupa, thousands of them. The paths around the site avoided the mass graves, but still there was the occasional human bone, brought to the surface in the mud of the wet season.

It was not only men who were killed, but also women and children. The motto was that treason must be eliminated down to the roots. There was a tree at the killing field where mothers watched as their babies were held by the feet and bashed to death against the tree. An appalling aspect was that both at the prison and at the killing field, most of the guards were teenagers, sixteen, seventeen, some as young as twelve. They were told, and probably believed, that these people were traitors and enemies. But there were cases where teenagers had to kill their own parents or brothers.

I said when I started that understanding the Khmer Rouge was a very hard thing. It has not become easier with the writing. The bounds of my understanding of the human spirit do not stretch enough to encompass this.

The end of the story came in 1979. Opponents of the Khmer Rouge, the ones not dead, began to slip over the border into Vietnam. The Khmer Rouge pursued them relentlessly, invading Vietnam. Vietnam responded by invading Cambodia. The army of the Khmer Rouge was so riddled by the purges that they could hardly fight. No contest. The Vietnamese entered Phnom Penh, and ended the regime after three years, eight months, and twenty days, a number every Cambodian knows by heart. Vietnam was sanctioned by the UN for invading and setting up a puppet government. Our French lady said that was crazy; Cambodia needed aid, not sanctions. But Sherek said the Cambodians were grateful to the Vietnamese for getting rid of the Khmer Rouge, but that they should have deposed the regime and gone home; staying made it an invasion. The Cambodian government was restored about ten years later, under King Norodom Sikhanouk.

Sorry to have gone on so long about politics, but this touched me.

The other major event in Phnom Penh was the visit to the royal palace. It showed the splendor beloved of monarchs since Louis XIV. Lots of pagodas and stupas in the palace precincts. Sherek says 90 percent of Cambodians are Buddhists. (The Khmer Rouge were anti-religion, and destroyed lots of pagodas and temples. Sherek though they might have been a bit less cruel had they believed in reincarnation.) When the French were displaced in 1953, rather than continuing to use the French coinage, the Cambodians melted down the silver francs (five tonnes of them) to make the floor of the Silver Pagoda in the palace complex. There were several crowns in the distinctive Cambodian style, and cloth-of-gold coronation robes. These last could be rented out for weddings - king for a day.

At Phnom Penh we left the Mekong river proper for the Tonle Sap river. The Tonle Sap is a large lake, over 100 km long, more than 20 km wide at its widest. The Tonle Sap River is actually just an extension of the lake, at the lake level. Tonle Sap is, in the technical sense of the term, a backwater. In the dry season, the river drains the lake into the Mekong, and in the wet season, the river reverses and fills the lake from the Mekong.

We visited a village primary school (grades 1-6) on the riverbank. A foreign NGO was sponsoring the teaching of English at this school, so we got to enjoy a bit of conversation with the kids. Kids tend to be kids the world round, and they are great. Just for kicks, they arranged to take us to visit the local pagoda by ox cart. "How did you enjoy the inaugural parade, Mr. Lincoln?" "Well, as the man said who was tarred and feathered and run out of town on a rail, 'If it weren't for the honor of the thing, I'd just as soon have walked.'"

We visited a pottery factory, and watched a lady construct a pot the traditional way, walking around the pot, rather than turning the pot on a wheel. They said she could make 50 pots a day, for a pay of about $7. This place also processed palm sugar, with about the same processes as used for maple sugar, except that the taps are at the tops of the trees, 15 meters in the air, and need to be tended every day. Guy said he could tend about 25 trees, and had been doing so for 45 years. Anyway, the palm sugar product tastes remarkably like maple sugar as well. They also made a palm wine which they distilled, into the rawest soft of moonshine. (At the rice crispy factory we were served a rice wine distillate, which actually tasted pretty good.)

Half way up the Tonle Sap River, we said goodbye to the Toum Tiou, and got on a speedboat. The speedboat wasn't really very speedy, though it moved right along. It was only a little faster than the Toum Tiou. What it had was a much shallower draft. The water is quite low, and there was some doubt that there was even enough water for the speedboat to get into the Tonle Sap. Taking the speedboat was good news - they said that if we had been forced to take the bus, it would have taken twice as long as the three and a half hour speedboat ride. So we crossed the length of the Tonle Sap, and went for a while slowly along a shallow canal, to reach Siem Reap. Siem Reap is just a few kilometers from Angkor, the capital of the Khmer kings who ruled a great empire for 500 years, the tenth to the fifteenth centuries. A Chinese visitor in the twelfth century estimated the population of the Angkor region at one million people. At that time, London had a population of thirty thousand, and Paris less than a hundred thousand. The cause of the decay of the Khmer empire is not entirely understood. In the 15th century they had a set of dynasties of alternating Hindu and Buddhist persuasions, which certainly did not help, but the killing blow is possibly some very bad drought years, of the sort that did in Chaco Canyon, a couple of hundred years earlier.

The Angkor region is amazing. The kings lived in wooden palaces, but built stone temples, whose size emphasized the grandeur of the king. Each king with royal pretensions built at least one temple. If you drive around the Angkor World Heritage site, every couple of hundred meters down the road there is another temple. Each temple is covered with incredibly detailed bas relief carvings. These served the same function as the stained glass windows in European cathedrals - to remind the populace of the founding stories of their religion. And, as in European cathedrals, these carvings do not have the whole connected text. They expected the priests to explain the stories, as a form of sermon. In the period in which the empire was being switched between Buddhism and Hinduism and back again, when Buddhists came to power, they proclaimed the figures above the gates were the four faces of Buddha, and installed statues of Buddha throughout the temples. When the Hindus came to power, they proclaimed that the gates represented the four faces of Brahma, and they knocked the heads off the statues of Buddha. So we visited four of the multitude of temples - Ta Prohm (10th century Hindu), Banteay Srei (10th century Hindu), Angkor Wat (12th century Hindu, converted to Buddhist), and Bayon (13th century Buddhist). Angkor Wat is merely the largest (by virtue of the king who built it having a very long reign). Its central tower rises 65m above the plain (and is currently topped by another meter of lightening rod). There is a marvelous bas relief mural of the Hindu myth of "The churning of the sea of milk." Before there was life on earth, both the gods of creation and the demons tried and failed to create the essence of life. Vishnu told them that the only way they could create life was to cooperate. So the gods seized the head of the great serpent Naga, and the demons seized the tail, and Naga was wrapped around an island in the great ocean. So first the gods would pull Naga to their side, then the demons would pull Naga to their side. As Naga was pulled, the island rotated, and churned the ocean into milk, from which the essence of life was created.

Banteay Srei, a relatively small temple, has the carvings in the best shape. They are incised up to two centimeters into sandstone; and done without an electric dremel. The finest detail must have been carved with a chisel little bigger than a dental pick. Bayon was built by the king after the war with the Cham, who had briefly conquered Angkor. Its murals depict scenes from the war, and many scenes from everyday life (which archaeologists find very helpful).

For any of these dozens of temples, one could spend years studying the carvings, ferreting out the meanings, and the religious implications.

We finally wound up the tour with a visit to another NGO funded school. Which again demonstrated how far Cambodia has to come - the government schools provide only the most basic education; poorly educated teachers often fail to show up; standards (yes, there are some, though one might have guessed otherwise) are poorly enforced, and many villages are without a school altogether. Progress beyond the sixth grade depends on paying a bribe to the teachers (it is called a special tutoring fee - ptui) Maybe the generation after the one we saw in this school will routinely receive a decent primary education. Half a century of peace it will take to achieve the economy and political system all countries deserve.

And so to home. With a security check at every stop. Siem Reap to Singapore to Hong Kong to San Francisco (stayed overnight) to Albuquerque.

Dog was happy to see me home.

Made a quick trip to Pasadena for my class 55th reunion. A little sad. There were about seven of us that hung out together a lot, especially as freshmen or do. Three are dead. One is deep in chemotherapy (I rather think the third or fourth round, so not good) and was sufficiently sick that he didn't want us to come visit. One, who dropped out before graduating and is therefore not technically in our class, lives in northern Calif., and didn't come down for the occasion. So, only two of us hearty and reasonably hale.

There were about 30 people, classmates, spouses, and significant others, from my class Thursday night. A rather less socially involved bunch than five years ago. Not many paychecks in the lot. That changes your perspective. Men being men, there were not many grandchildren photos being circulated. Although there were women grad students in the 60s, I believe the first women undergrads came along about 1970. I expect they will change the reunions as much as they changed the student body.

Friday noon was the Half Century Club luncheon, open to anybody who had been a grad for 50 years or more. The 50th reunion guys had special orange name tags, calling them out. The young guys. The rest of us tended to ignore them a bit. But the luncheon was a plentiful source of examples of people who walked slower than I do. (I think I'm still on the long side, though, of the time needed to get out of a folding chair.)

That afternoon, went off to Huntington Gardens, Library, and Art Gallery. We got showed a bunch of plants in the gardens. But actually I think the jacaranda trees in glorious purple bloom all over Pasadena were really the botanical highlight of the trip.

I went in the gallery especially to see the "Blue Boy" again. I really like that picture, and not for the reasons given in the literature, which mutters about technical mastery and a new direction given to English painting and so on, but because, in that large room full of portraits of people in fancy clothes, he was the only one who looked like there might be something other than vacuum behind that high white forehead. There are people who happily read the character of the sitter from his portrait. I doubt it. In some cases, and Blue Boy is one, one can read what the artist thought about the character of the sitter. But if the artist is good enough to put that in the portrait, he is also good enough to leave it out, which is often the safer course, in terms of repeat business. The only other portrait I particularly noticed with a personality rampant was a portrait of the Misses Constable, sisters of the artist. And there, the sitters are unlikely to kill the artist, no matter what.

Saturday was Alumni Seminar day. All-in-all, I wasn't very impressed. Except for a couple, they were pretty well rehashes of stuff that was long published and well known. The exceptions included the South Pole experiment that measured the curl of the polarization in the Microwave Background. The project leader didn't talk about the result, which has been discussed well beyond "to death" on the preprint server, but about the machine he built to make the measurement, which was really cool. The other good lecture was by a historian talking about the status of women in the early days of the republic, and why there was no explicit mention of women in the constitution. She compared the status of women, rather unfavorably, with that of slaves.

That night we had the reunion of my undergraduate house. This was open to all years. So I caught up with a couple of guys who were from the year ahead of me, who flunked out in their junior year, and who came back for a second junior year in my senior year, and graduated a year behind me. The event also included current undergrads, which was especially interesting. Overall, I think the house has become rather more civilized, due to the addition of women, mostly, but also to a consciousness that binge drinking is not a good thing. Some traditions are still going strong. For instance, anybody being particularly obnoxious can expect to be seized and carried to the nearest shower. (Slight modification: they are now given the opportunity to divest their cellular phone on the way.) Some traditions have dropped by the wayside. Having women at Tech means that all the exchange dances and parties with heavily or entirely female colleges have essentially ended. And the current undergraduates no longer dress for dinner. (We wore coat and tie; often grubby and sometimes tokenized, but coat and tie.) Perhaps most interesting are changes in language. Our common usage "snake", verb intransitive, meaning study, was unknown to them. (In my day, the word "study" was almost unused.)

I decided to go to the meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Boston, mainly for the opportunity to hang out with my son Bill and his wife Ann for a while. Turns out that the refugee they have been fostering, Bawi, was having his high school graduation the Sunday before, so I traveled on Saturday to show up for that.

Bawi is even more terse than I am, so I didn't get much feel for how he feels about graduation. I think his terseness arises from the time when he first arrived in this country, and spoke no English. He found he could get away with saying 'Yah' whenever somebody asked him a question without his having to understand it. Still, he seemed pleased with the whole thing.

As usual, there was a good deal of speechifying at the ceremony. A couple of the speeches were delivered by students. These were, at least, rather more ernest than the others. There was a very competent orchestra which folded their stands and stole away immediately after the "Pomp and Circumstance". There was a choral group which sang only one number. Personally, I'd have preferred more music and less speech. But then, I'm a stranger, and maybe the graduates enjoyed the oral encomia.

There were a couple of hundred students, all carefully lined up in alphabetic order. I recall one of my graduations that took a more sensible tack. They handed us a piece of paper, on which we wrote our names. Then, when we got to the stage, we handed the paper to a name reader, who read it out as we walked up and shook hands with the president, who gave us a prettily rolled and beribboned piece of blank paper. We picked up the actual diploma after the ceremony.

The program for the event called for a couple of speeches after the parade of graduates, but the speechifiers apparently recognized the incredible futility of that, and begged off.

The Astronomical Society meeting was in a hotel downtown. I took public transportation, which, it turns out, worked very well. Bill was slightly horrified that I took the bus (recommended by Google), twenty minutes walk from his house, rather than accepting a lift to a train station. But, as I said, it worked very well. I rather enjoyed sitting in the comfortable bus and watching the freeway imitating a parking lot.

Lunch at the meeting was usually at Au Bonne Pain. The first day, I went there because it was closest, and had their salad bar. Second day I went there because after filling my plate the first day, I discovered they had other very tasty looking things to eat. Third day the observatory director took me to lunch. (He takes people out to eat solo or in very small groups regularly, I think to offer them a chance to complain in a relatively private setting.) Fourth day, back to Au Bonne Pain, because it was raining, and it was the only place I could get to without going outside. Never made it to the intriguing looking hot dog stand on Copley Plaza.

The meeting itself was sort of medium useful. Nothing very dramatic, but some nice reviews. It was a special meeting for the Laboratory Astrophysics Division and the Solar Physics Division, neither of which much turn me on at the moment. One of the more interesting talks was about the project to digitize the Harvard Plate Collection, of patrol camera photographs of the sky spanning more than a century. So you can find what your favorite object was doing the while, plotting perhaps 10,000 brightnesses over a century.

On the way home, we had the biggest bump I've ever had in a commercial jetliner. We were flying through clouds and got into really severe bumps for about a minute. Then we came out of the cloud and could look off to our right and see, on a level with us or slightly above, the characteristic anvil shape of cumulonimbus. There were a few screams in the plane, but I thought they smacked more of "roller coaster" than "terror".

Went for a walk in the Magdalenas yesterday, first time in over a year, since I fell down and hurt myself last summer. Went up Copper Canyon. Got tired and didn't make it to my objective, the ruins of an old log cabin. I think it was only three or four hundred yards more, but hey, it was uphill. Anyway, just under five miles round trip.

Weighed myself after I got home, and was seven pounds short of nominal. So I immediately quaffed two liters of fluids; I guess I owe my body another liter today.

Cast of Characters: Clarkberg family - Marin, Lawrence, Jasper (19), Thea (14). Zilch family - Pam, Brad, Sydney (12), Quin (9). Judy Saltz - Pam's mother, stepmother to my stepchildren Bill Clark - my son. Wife Ann stayed in Mass with her mother

I went off to spend Christmas in Philadelphia with Judy Salz and Pam Zilch and family. I flew out on Sunday, my daughter Marin came down from Ithaca on Monday, and Bill came from Boston on Tuesday.

Monday Judy and I went to play bridge at her bridge club. Other than that two hours, I can't remember doing anything.

Tuesday we met Bill at the train, and went out to dinner at Marrakesh, a Moroccan style restaurant.

Wednesday was Christmas Eve. We made posole at Judy's house while Pam and family went off to Brad's parents.

Am I giving the impression that we had a pretty inactive and relaxing time? Could be.

Thursday we had Christmas at Pam's house. A little less frantic than some Christmas mornings, because of the lack of any very young children. Quin is nine, the youngest of the lot, and the only real child among them, though the rest of them, even Jasper, could act like a child at times. Quin has beautiful, shoulder length hair. It made me think of Harald Fairhair, a medieval king of Norway. (His nice hair and nice cognomen did not indicate a nice disposition - medieval kings are not known for enlightened government, and Fairhair was somewhere below the middle of the pack.) Perhaps the signature Christmas toy was a set of small rubber chickens, designed to be fired like rubber bands from your finger.

Then we went off to three days at Cape May, to give Thea a chance to walk on the beach, an experience she claimed to be lacking. We picked up a few shells and nicely rounded stones. We went to the Cape May lighthouse, which was interesting. They made a big point that brick lighthouses have to have well designed ventilation, or the mortar gets wet and disintegrates and the lighthouse falls down after a couple of decades. The light was designed to burn whale oil, but soon converted to kerosene. There were four wicks burning near the focus of a Fresnel lens. I, like an idiot, forgot to ask about the mechanism that turned to lamp - some sort of clockwork I should think - which would have been interesting to know.

We went to see a rich guy's house circa 1900. I wasn't much impressed. It stood out for neither excess nor historicity.

I was delighted that Thea was studying the Mongols in her 9th grade AP history class. They went into it deeply enough that had I not myself recently taken a refresher course in the history of the Steppes I would have totally at sea behind her. She was well up on Temujin and his large and talented family, who were a foundational force in Asia, Asia Minor, and Eastern Europe for half a millennium. She was aware of the organization of the Mongol armies into tumen, each a cohesive and disciplined force of 10,000 mounted archers, under the command of a captain general who was usually a relative of the Great Khan. Later, sometimes two or three tumen, or even just one, broke off from the Khaganate and became countries in their own right. The Mongols conquered and assimilated into the great Asian countries of the time - China (Temujin's grandson Kublai), India (his great grandson Akbar), Iran, Kushan, and the southern steppes of Russia. The only thing that stopped them was not having good grazing for their horses.

I approve of that sort of pedagogy, to take a topic not well covered in most history courses (below the 300 level anyway) and go into it in depth. Learning how to study a subject is at least as important as learning the facts. Not being able to rely on "well, everybody knows..." emphasizes the art of learning.

Got back home to Socorro for the first real cold day of winter. Sixteen when I got up Wednesday morning.

Attended, by video, the Albuquerque Unitarians' "Coming of age Ceremony". Graduation from 8th grade. Sort of a ba[rt] Mitzva. It was interesting. The UU religious education program tends to attract the kids who don't do well in other assemblages of their peers.

There was a severely learning disabled kid, who didn't talk, but beat time to some music on his wheel chair. The there was the Aspergers kid, who said "My chronological age is 14. My intellectual age is maybe 18. My social age is about 4, if that." Then there was the kid who started off his presentation with "I am an atheist." Saying that in front of a couple of hundred people takes guts, even if he was supported by his parents, which he probably was, considering what Unitarians are.

There are lots of Unitarian subgroups, of which the Atheist Unitarians is probably the largest, though they call themselves Humanist Unitarians, to better attract the agnostic set. Albuquerque is said to have an active group of Wiccan Unitarians, though I haven't talked with one. I do know a Buddhist Unitarian. I've briefly chatted with a Hindu Unitarian; probably a Vishnaite, which I say because she sounded nothing like brother Bill, who is a Shivaite. But then, who does sound like Bill? We have a Muslim Unitarian in Socorro. From chatting with her, I think she may be Ahmadi. Relations between the Ahmadis and mainstream Islam are tetchy at best, which may be why she finds the Unitarians more congenial than the local Mosque. Our senior minister expresses great admiration for the Tao Te Ching, though I would not go so far as to call her a Taoist.

In the hands of corrupt priests both Buddhism and Hinduism can become great bundles of appalling superstitions. The Mahayana Buddhism of Cambodia seemed to me especially short on education in moral principles in favor of random folk tales. Christianity seems to do somewhat better about this (at least since Martin Luther), as does Islam, and I rather think Tao is hardly at all susceptible to that sort of corruption.

Went off to Big Bend over the Memorial Day weekend. Been thinking for a long time that I should visit something that near. Spent Saturday night in Alpine, TX, home of Sul Ross College. Worried a bit about getting a room in a college town this near commencement, but motel occupancy seemed to be low.

Spent most of the day Sunday in the Park. The big thing the literature said that I didn't pick up on was the large temperature difference between the River and the Park Headquarters, up in the Chisos Mountains. In the morning, the temperature seemed pleasant, so Dog and I went walking a mile or so down something called River Road East. (We had to walk down roads, per Park rules, because the Park Service hates dogs.) Time we got back to the car, it was 11 AM, and spending the rest of the day in an air conditioned car seemed like a good idea.

Despite the ominous warning "Four wheel drive required", what we had seen in the first mile or two of River Road East looked pretty mild, a good low speed passenger car road, wide enough to turn around in if it suddenly became otherwise. So we set off driving down River Road East, and did a right turn onto Glen Spring Road, which led back to near the Park Headquarters. And the road was pretty good for two thirds of its length. The middle third was a bit hairier, and if I'd had another couple of inches ground clearance I would have worried a lot less. We then drove around the Chisos to the west end of the Park. From there one can get a glimpse into the vertical walled Santa Elena Canyon, featured in the literature. Actually, the north wall falls away, and at the point the road ends, you see a long stretch of the near vertical south wall, as well as being able to see into the narrow gorge.

From there, another dirt road, Old Maverick Road, runs back up to the Park entrance. This one didn't demand four wheel drive, and indeed had stretches one could get up to 30 MPH. There were also some bumpy spots.

When I get tired I have an urge to go straight home. The urge to avoid the hassle of checking into a motel outweighed the thought of a leisurely dinner and a quick shower. So we got home about 11 PM Sunday.

Went to my highschool class 60 year reunion. I'm afraid it's turning into a bit of a tontine. Everybody says they're well and good, unless you directly question them, which isn't much my style. Still, we're doing pretty well. The memorium page is only about a third of the class. And, as I said, they look pretty good. One spouse of a member in a wheel chair, and one class member who would have been happier if he had been. Good turnout of nearly half the class. A couple of them known to be too sick to travel.

The main event was going to the musical "Texas" in an outdoor amphitheater in the Palo Duro Canyon. This show runs twice weekly during the summer, and apparently still draws a good house. They said attendance was just over 1000 - nearly a sellout. The show is an "Oklahoma!" wanna be with a distinctly High Plains accent. It was composed specifically for this amphitheater. The composer threw in a lot of folk music, hoe downs and the like, and, apparently to lend a bit of cosmopolitan flavor, a bit of Beethoven's "Ode to Joy". They had Quanah Parker presenting the red man's viewpoint, though what he said sounded more like an interview I read with one of Buffalo Bill's Sioux than what I would expect of a Comanche. They also had a first class fireworks show, nearly the equivalent of Socorro's Fourth of July.

As I've done each reunion, I walked the Lighthouse Trail in the Palo Duro. Both the trail and the steep pitch at the end were noticeably tougher than last time.

I was burgled, and lost my laptop. Nuisance.

So I went off to Hawaii for a meeting of the International Astronomical Union. First thing I noticed about Hawaii is that there is about a ten degree difference in the comfort index from what I'm used to. That is, 85 F in Honolulu feels as uncomfortable as 95 F in Socorro. And it seems to be more common. My hotel was about a mile from the convention center and I arrived totally sweaty both morning and evening.

This is a big two week meeting, with about six or eight parallel sessions for five hours a day, and a general session for another hour and a half, and occasional other activities. The organizers didn't do very well at the parallel session business. In the second week there were often three simultaneous sessions I would have liked to attend, whereas in the first week I was sometimes a bit hard put to find anything interesting. It turns out that I have a bit of a low tolerance for seven talks in a row that all start out flashing the same slide and saying, "This is the Schmitt-Kennecut relation, and now I will tell you why it looks this way." I must admit, though, that there was a good deal of variety in what followed.

There was one interesting day the first week, a meeting of the Working Group on the History of Radio Astronomy, otherwise known as "the old fart's session." This included a lot of my friends.

The weekend between I flew across to Hilo to tour Volcanoes National Park. Hilo is a good sized town, 40,000ish people, which lets it support an airport with commercial jet service, and a park that is a really lovely Japanese garden. However, the general ambiance is totally Socorro-by-the-Sea. I could move there, if it weren't for the humidity.

The tour of Volcanoes Park was interesting. We didn't get to see any lava actually flowing. (They said there was some, but the roads to get to where you can see it were closed.) There were various cracks and vents. The ones driven by ground water seeping onto hot rocks were pretty innocuous, and they let us walk right up to them. Felt much like going into a commercial laundry. The guide said it was being cooled by the breeze that day, and clouds of mist were forming down in the throat of the vent. Often, the superheated steam gets three or four feet above ground before condensing into clouds.

The vents powered by water closely associated with the lava were treated with more respect. We walked down to a set called Sulfur Banks. Despite rather fierce warning signs about sulfur fumes, including a set saying that you probably don't want to inflict this on your small children, they were really pretty tame. Only one small stretch of trail yielded a good whiff of sulfur dioxide, and a longer stretch where you could detect a faint odor of hydrogen sulphide. Both well short of what we got playing with the sulfur in our chemistry sets as kids.

Philosophical aside - as you go through life, always remember to stop and smell the sulfur.

We walked for a while on a lava flow that had been laid down in 1969. This was impressive by its ordinariness. Little more than half my lifetime ago this was a popping hell. Now it was pretty ordinary smooth-ish rock, covered here and there with a bit of sand that was really ash from a 1974 eruption a couple of hundred meters away. There were already ohia trees and ohelo bushes growing on it, apparently totally without benefit of soil.

The crater in the floor of the Kilauea caldera was smoking right along. The guide said that sometimes when the wind was wrong they closed the road we were on. The Kilauea Iki crater, a 1951 eruption a couple of miles from the caldera, now has a hiking trail running down the middle. A couple of mile hike, which we didn't have time to assay.

Since I was staying in a hotel in Waikiki, I of course had to go down to the beach for a swim. The water was OK, the bathing suit full of sand somewhat less so.

The trip home was a bit of a hassle. American Airlines and US Airways have merged, and that weekend they were combining some of their operations. As a result they were not operating as smoothly as a well oiled machine. We left Honolulu as scheduled about 1 PM. My schedule called for changing planes in Phoenix, getting on a plane to Albuquerque at 11:50 (hey, that's only 9 PM Hawaii time). When I arrived at the gate, the sign was saying "ETD 2:30 AM". Sometime after midnight a plane actually appeared at our jetway, which seemed like an encouraging sign. However, at 2:00 they announced that they were unable to round up a flight crew, and started handing out hotel vouchers. They also gave us a card with a phone number, which they said was a special operations office who would make arrangements for our flight on to Albuquerque. We then went downstairs to wait for somebody to rescue our luggage to take to the hotel. While there, I noticed a lot of fellow passengers wandering around with phones to their ears and "on hold" looks on their faces, and concluded that special operations didn't really have the people to handle an entire airplane all at once. So I forbore calling until I got to the hotel, where a modest wait resulted in an agent telling me I was booked on the 9:45 PM flight Sunday. So Sunday morning I went back to the airport, and after a couple of less fortunate encounters I would up with a very understanding agent who checked my bag without charging me the $25 luggage fee and put me on standby for the 3:15 PM flight. So after a leisurely lunch at a pretty good airport restaurant, I showed up at Gate B9 about an hour early. Nobody at the desk. A half hour on there was an announcement of a gate change - the Des Moines flight had its gate changed to B9. After a good deal of confusion and milling about we managed to provoke an announcement that the Albuquerque flight had its gate changed to B7. The sign at that gate said "El Paso". After more queries, they said the Albuquerque flight would leave from there after the El Paso flight left. Except the person at the desk there told us the Albuquerque flight would leave from Gate B9. The person at the desk at B9 said she had no idea where the Albuquerque flight would leave from. Some time after that, there was a gate change announcement that Albuquerque would leave from Gate B3. So we went and hung around B3 for a while (the sign there said "Austin"). After quite a while, they announced the Albuquerque flight would leave from Gate B7. There the people told us that the airplane then unloading would take us to Albuquerque. (The gate sign still said "El Paso"). Fine, except the person at the desk claimed I wasn't on the standby list for this flight but on the 6:30 flight. So people started getting on the airplane. I hung around until the line cleared out and went, with two or three other problematic cases, to hang around person manning the gate. She pressed a couple of keys on her computer and handed me a boarding pass, which I held to my breast as I sprinted (in relative terms of course) down the jetway before they could change their minds. We finally took off at about 7:00.

So I had little time to recuperate before showing up at the office Monday morning. And little time to catch up there before I got word that my sister Betty Pucket had died. So on the Thursday I was off again to go to her funeral. For somebody at age 94, funerals are not so much a time of grieving as an acknowledgment of a long life well lived, and a celebration of the continuity of generations, as the old goes to make way for the new. (Bill would say a celebration of the Lord Shiva.) I had a very nice time seeing my three nieces all together (it has been decades since I've seen Maggie). And I saw my great nephew Jason, who went to New Mexico Tech, and I had gotten to know as a very nice guy.

Only travel adventure there is that I rented a GPS with my car, because I have had trouble before finding my way in and out of Love Field. I would have thought it very secure that the GPS would know its way back to its livery stable. Wrong. It informed me that its home was in a gas station/convenience store four or five blocks away. I was past the Love Field turnoff, and had to spend six or eight minutes managing to get myself turned around again. Between that and a couple of Dallas-type freeway clogs, I managed to get to my gate, with my boarding group B pass in hand, just as they called boarding group A. Perfect.